THE BLOG

Incentives, #SpaceAsAService, and the coming Golden Age of Real Estate

The Meagre Company, an Amsterdam militia group portrait or schutterstuk by Frans Hals and Pieter Codde (1633-37)

Incentives matter. As every practitioner or student of business knows, the way we operate our companies is largely driven by the incentives that our business models dictate. Where you are on the classic S curve of business maturity really matters.

At the bottom left of the curve you have little competition, but not many customers, and as you move up the centre of the S you have more competition but enough customers to keep everyone pushing on and profitable. By the time you get to the top right of the S you have all the customers you are ever going to get but masses of competition. You start in an agile, constantly iterating world and end up in a static, commoditised one.

During that business lifecycle your incentives vis a vis boosting revenues or cutting costs change entirely. There is a reason why you often get great service and value from a startup but rotten service and poor value from a utility. One is incentivised to get you to buy into their brand, in the hope of becoming a repeat customer, and the other is just incentivised to exploit their monopoly power and extract as much money from you as they can.

The upside of this process is that as one S curve reaches the top right, the seeds of the next S curve are bubbling away, and the monopolist relatively quickly gets ‘disrupted’. Technologies change, innovations occur and, as consumers, we find we get offered something better, cheaper, faster. It is the very point of capitalism.

In real estate though this process has never really worked. The office building has not, fundamentally, changed very much over many decades. Barring notable exceptions they have been all much of a muchness; grey decor, grey desks, grey computers and black chairs. You had posh versions of dreary offices and ordinary versions of dreary offices. And this worked beautifully for the industry; all the incentives pointed towards doing the same as your competition. The sheer dullness of corporate offices was a feature, not a bug. In short this setup worked, and worked well. At least it did for landlords.

That world though is about to be blown apart by the rise of #SpaceAsAService, and all the incentives the real estate industry has worked to for decades are about to be changed.

And this is a great thing.

The two biggest changes are around customers and product. First, the most important feature of #SpaceAsAService is that the customer of a landlord morphs from being the name on the lease and the person who signs the quarterly rent check, to every single person who enters into their property.

When occupancy is on-demand, or at least by way of short term leases, the incentive to keep on pleasing the users, day in day out, suddenly becomes of paramount performance. In a long lease world the incentives are to let as much space as you can, for as long as you can. And thereafter your incentives are to not spend a cent more than you have to to fulfil your lease obligations. In a #SpaceAsAService world these incentives are turned inside out; you really want to lease less space, per person, and in many cases for as little time as possible.

Completely on-demand space carries a significant price premium so in an ideal world, if you maintain high occupancy with a high % of on-demand usage, your returns would be optimised. Obviously that price premium reflects the higher risk to the landlord, but again the incentive then is to minimise this risk by providing the greatest possible user experience. For the specific type of customer segment you are targeting.

And that is why product is the other great change, alongside the nature of the customer. Only the best spaces, the ones that really do provide the product or service that a user needs as and when they need it, will pull off this business model. They will need to understand exactly how their buildings are operating (environmentally as much as anything else), how exactly they are being used (which areas are quiet or busy, popular or underused etc) and also exactly who their customers are and what are the ‘jobs to be done’ that they need appropriate space to help them get done.

In short, in a #SpaceAsAService world all the incentives for a landlord are aligned with providing fantastic workplaces where the user experience of everyone who enters their properties is so perfectly attuned to their needs that they keep coming back, and are prepared to pay a premium for.

This is why we are entering into a golden age for commercial real estate; everyone is now incentivised to be better than everyone else. And that is quite a flywheel.

Antony

How should Landlords respond to Flexible Workspace Demand? Are you a Pig or a Chicken?

CBRE Research recently put out a report titled ‘UK Landlords & Investors Embrace the Flexible Revolution’. In it they write, ’77% of survey participants are currently considering some form of flexible space provision’. Whilst UK centric one suspects the results would be similar elsewhere, especially in the US.

My first thought? Wow, #SpaceAsAService is now rapidly moving into the mainstream.

My second thought was about bacon and egg sandwiches…

‘What’s the difference between the Chicken and the Pig in a bacon and egg sandwich?’

‘The Chicken is involved but the Pig is committed!’

Knowing who you are as a Landlord is vital with #SpaceAsAService.

‘We’ll do flexible space ourselves’ is something one hears a lot from Landlords. According to the CBRE report some 35% of Landlords say they intend to self operate their flexible space. If any of those 35% are Chickens they will fail. The problem is that making #SpaceAsAService work is as much about mindset as a real estate problem.

Do you REALLY want to go from being ‘a rent collector to a service provider’? REALLY? The former is a very different type of company to the latter. Product companies are organisationally, financially, culturally very different to service companies.

In tech think of Google vs Apple; one is a service company the other a product one. and they have very different busines models, cultures and attitudes. Or take WeWork vs the UK’s largest REIT Landsec - they are from a different planet! Their customers, competitors, networks and ecosystems are all different.

For a traditional real estate company to become a successful #SpaceAsAService company is a HUGE challenge. One cannot be a bolt on to the other. Only Pigs will win in this game. Commitment is everything.

BUT being a Chicken might well be a much better move. This is not a good or bad issue. The point is, you have to understand what you are and what you want to be. If you are a Chicken then fine, but do not kid yourself that you are a Pig.

If you read the phrase ‘Real Estate is no Longer in the Business of Real Estate’ and immediately go ‘Yeah’ then do your own #SpaceAsAService - if not then partner with the best operators you can find.

If you see data analytics, IoT, AI, network effects, BIM, mobile apps, ecosystems, UX, Branding, B2C and hospitality as core skills within real estate then do your own #SpaceAsAService - if not, partner.

If you see your customer as being the name on a Lease, and your billing cycle as being quarterly, and your company is optimised for that, then partner for #SpaceAsAService.

Startups always moan about companies that don’t quickly adopt their products or services. “They just don’t get it” they say. This is almost always wrong. They get it perfectly well but their companies are optimised for their business model. Not the startups. And rightly so. That is why change is so hard; they are operated for business as it is, not as it might be.

Mostly, real estate companies are optimised for being Product/Rent Collector companies. As they should be. That is what has worked for several decades. Build or buy an asset, lease it, keep it or sell it. And many are very good at that; the concern is that many will forget what they are, and think their slick machine will work in a different world. It won’t.

And that is NOT a criticism. Optimising for what you are is what all good management does. But at times like now, when a market is ‘fundamentally’ changing, the chances of value destruction are greater (perhaps) than value creation.

The #SpaceAsAService world we are entering is much more like the Technology than the Real Estate industry, and in tech ‘winner takes all’, ‘monopoly’, ‘market domination’ are the AIM. Networks/Marketplaces are where the value lies. The best space, with no network, will not come out on top.

Successfully networks win because they become the safe, comfortable and painless solution to a need. And they grow exponentially; from no-one knowing anything about them to suddenly being known by everyone. But once established their value grows exponentially as well. People are tribal, we like to belong. Only Pigs will build #SpaceAsAService networks we want to belong to.

There will be many winners in a #SpaceAsAService world, Chickens as well as Pigs.

Just be sure you know what you are.

Antony

Rain, Steam and Speed V4: Why, and how, technology is upending the real estate value chain

Rain, Steam and Speed, JMW Turner, 1844

This is the text of a talk I gave at The Chairman's Dinner, prior to the Urban Land Institute's Annual UK Conference on the 4th June, 2018.

There is an old Danish proverb that states ‘It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.’ So… obviously I am going to now make a lot of predictions.

Worse than that I am going to make predictions with a five year timespan. As any sane ‘futurist’ would tell you the trick to making predictions is to make them for a long time in the future. That’s why you have ‘the end of the world is nigh’ not ‘the end of the world is tomorrow’, as in the Monty Python sketch.

Near term predictions can make you look very stupid.

But I have a trick up my sleeve… and that trick is technology.

You see, within the tech sector, there is a very well established and pretty much rock solid adoption map. You start out with a product that gets picked up by innovators, and there are always some of them for just about every product, and then with a bit of luck you build a user base amongst the ‘early adopters’. Very soon after that though you reach what Geoffrey Moore, in his great book ‘Crossing the Chasm’ described as… the Chasm. This is where you come up against economics; you need enough traction to fund, or raise the funding for, continued growth.

The other side of the chasm is the ‘Early majority’ which is a market significantly larger than the early adopters. But most products never make it across the chasm. For whatever reason they fail to get enough traction to escape the world of startups. Just like some birds jump the nest before they are able to fly.

BUT for those that do Cross the Chasm, you know what their market development is going to look like. Growth amongst early adopters takes them to about 50% market penetration, and that is normally where they peak in terms of gaining new users. After that it is a matter of hoovering up the late majority, and even later, the laggards.

So, looking at life through a tech lens, yes you can predict the future. You just need to determine which products have ‘crossed the chasm’. Yes there is still the issue of determining speed through the stages, but far less uncertainty of outcome than is often assumed.

What has happened over time is that adoption of new technologies has got faster and faster. So, for example the Internet rose to 50% market penetration far faster than did electricity, the telephone or indeed the washing machine.

In similar fashion it took mobile phones about 17 years to reach 100 million users. The internet took about 8 years, and Facebook just 5. All though are knocked into a cocked hat by the Indian phone network Jio that reached 100 million users in just 170 days, after its launch in September 2016. That’s what free voice and data can do!

We can then see where the near future is headed, and we can be assured that it is going to get there faster than we think.

Last week I gave a talk and used Turners 1844 painting Rain, Steam, Speed for a slide. This is the one where the steam engine is flying across the Maidenhead bridge on the recently completed Great Western Railway. It sums up brilliantly what it must have felt like to Victorians caught up in the First Industrial Revolution. The future rushing towards you and everything in a bit of a blur. But with a feeling of palpable excitement.

That was then and this is now.

Generally speaking that feeling of palpable excitement has diminished, in many cases to be replaced by a feeling of angst and consternation. What were the election of Trump and the vote for Brexit if not a reflection of angst and consternation.

What has also diminished though is an appreciation of just how fast technology is developing, behind the scenes. As Jeff Bezos has said, we are all only impressed for a short while. So, even though you probably all have in your pocket a smartphone that in 1985 would have outgunned a Supercomputer and cost $25 million dollars, you don’t give it a second thought. Whereas 25 years ago you could wait 28 days for a mail order delivery, we now complain that our Amazon order only arrived at 8pm on Sunday, as opposed to 8 am. After all we did order it from our sofa whilst watching a streaming movie 24 whole hours ago.

And that is the flashing red light for the real estate industry.

Regardless of whether or not the populace is viewing technological change through the excitable lens of Rain, Steam, Speed, it is happening faster than ever.

And that is why our safe, if cyclical, slow world of real estate, where you build something you designed ten years ago, largely unchanged, and with no penalty, is set for a disruption that very few believe possible, let alone likely.

The key reason this is both possible and likely is that, contrary to many peoples understanding, human behaviour follows on from technological developments and not vice versa. Technology is not invented in response to human demand. Technology is invented when its invention is possible.

For example, you probably remember the dot com crash of 2000 where trillions of dollars of investment capital evaporated over the following year. Much merriment was had at the tens of millions lost by online pet food companies and video on demand operators. What you might be less likely to know is that the online pet food company Chewy was sold for $3.35 billion last year and that Netflix is currently valued at $153 billion.

The difference? Infrastructure.

In 2000 broadband was in about 26% of homes, and computer chips contained about 100 million transistors. Today broadband is near ubiquitous, at about 96% penetration, and computer chips have 10 billion transistors.

Chewy and Netflix exist because they can exist, not because any human asked for them.

The technology that crosses the chasm does have to either address an existing need or create a new need, but most importantly it needs to work, at least in the context of something users value. For example, the original iPhone was a terrible phone, as Microsoft’s Steve Ballmer very loudly shouted about as he mocked the then not very important Apple. But Steve Jobs knew that people loved being able to take their music around with them and loved taking photos, and on those two vectors the original iPhone was terrific. That took it across the chasm.

It is really unwise to bet against progress in technology.

A few years ago there was much talk about Moore’s Law coming to an end. This was the theory, from Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, that technology at a given price would double in power every two years, and it had held for fifty years. The talk though was that because of the laws of physics transistors simply could not get any smaller and 10 billion on a chip was about the limit. The logic seemed hard to refute. But things have not panned out like that. Instead of progress getting slower, it has sped up.

And for that we have to thank the computer gaming industry.

With a fortuitous twist of fate, it turns out that the type of computer chips that Artificial Intelligence works best on are not the PC chips that Gordon Moore and Intel had been referring to but GPU’s, which are the primary processing units for dedicated gaming machines. Simplistically, in computer games it is vital to be able to do thousands of things at the same time, as opposed to one after another, and that encapsulates the difference between GPU’s and CPU’s.

The consequence of this, the use of custom designed chips to do very specific tasks is that the training of Neural Nets, which are foundational to Machine Learning, increased in speed 60 times in just three years from 2013 to 2016, with the bulk of that happening in one wonder year, 2015.

At the same time the scale of the smartphone industry has increased so dramatically that the cost of any component in one of them has reduced to being ‘cheap as chips’, as the saying goes.

So any sensor in a smartphone, for example GPS, accelerometer, proximity, barometer, biometric, compass, and of course high definition slow motion and high speed still and video cameras is now available in very high quantities and at a very low price.

Combine all of this together and we are entering a world where anything that is ‘structured, repeatable or predictable’ is going to be automated, and if you believe McKinsey, they said in January last year that that applies to 49% of all the tasks people across the globe are paid to do.

The RICS last year published a report saying that 88% of everything a surveyor does could be automated within 10 years.

Does that therefore mean that half of all jobs are going the way of the Dodo and that Surveying might not be the best choice of career?

In short No - because life never works out like that. What it does mean however is that the work we all do, and the way the economy works, will change fundamentally and in so doing will upend the value chain within the real estate industry.

Lets go through some of the sectors:

The Office:

When half the tasks that humans do now are no longer within the purview of humans, and anything ‘structured, repeatable or predictable’ is done, in one way or another, by a ‘machine’ the fundamental purpose of an office changes. ‘New’ work, as I like to call it, in a digital world will be all about human skills. Design, Imagination, Inspiration, Creation, Empathy, Intuition, Innovation, Collaboration, Social intelligence - those are the killer skills of the next 10 years. And they require a new form of office, one that harnesses data and design to catalyse just those skills.

42% of employees work for companies that employ over 250 people. Those companies should be able to muster up the investment, inclination and skill to create the sort of ‘Imaginarium’ that allows their employees to be as productive as they can be. As we know, many of them fail on this at the moment but my feeling is that the top two quartiles will create great spaces in the future, if only because without them they won’t be able to hire the talent without which they will collapse. Faster than ever before.

But 48% of people work for companies that employ less than 50 people, and in many areas, such as the City of London, some 70% of occupied units are less than 10,000 sq ft. 50% are less than 5000 sq ft.

In these companies they most likely will not have the space or skills, even if they do have the inclination, to create great modern, flexible, adaptive, high quality, human-centered spaces.

My prediction is that this sector of the market is a prime target for whoever can come up with the business models and #SpaceAsAService thinking that delivers a Product that fits their requirements. ‘Everyone deserves a fantastic workplace’ to quote Neil Usher, but most small companies, half or more of the market, cannot deliver this for themselves. Someone needs to do it. And whoever does it best will build a great Brand with great value.

The flip side of this is that there is going to be a huge amount of obsolete space around. We need fewer but better offices.

From an investment standpoint the big trend will be the shortening of leases, and the increasing change from a valuation model with bond like characteristics to one where the operator really matters, as they will be the driver of revenue. The curator of the user experience, the UX, will be perhaps the most important component of an investment. The owner of the asset, if not the curator, will move down the pecking order.

Retail:

In the same way that, if we admit to reality, we do not need offices to work, we do not need shops to shop. In both cases we need to be made to want them. It is interesting to see and hear the attention the Grimsey Report 2 is getting at the moment. Five years ago I was at the launch of the original report at the Houses of Parliament. Thereafter Parliament completely ignored it, whilst indulging in endless fantasies about ‘saving the High Street’. That was an obvious wrong move five years ago and thankfully today you hear less nonsense along those lines, even if not a great deal of coherent action.

The reality of retail is very simple. Mostly shopping is dull, if necessary. For those essential items that we forget about and run out of, and for anything ‘cheap’, too cheap to ship, that we want or need to buy, there is a solid future for physical outlets to supply. At the other end of the market, for shopping that is fun, we both need and desire great retail experiences that pander to our innate human need to socialise and acquire. Everyone, or almost everyone, loves some form of shopping. Give them a great experience and they will part with their cash.

For everything in between cheap and everyday, or fun and an experience, we can rely on Mr Bezos to handle it.

Amazon spent $13 billion on Whole Foods and Alibaba have spent $9.3 billion on offline retail. Do not be misled by this - they have not done so because they think offline retail is great and an essential asset. They have done so because, with their vast technological capabilities, mountains of data, and personal relationship with millions upon millions of online shoppers, they believe they can build a ‘New Retail’ model that is much superior to what the incumbent offline industry provides.

The thing to worry about is whether the software industry can learn retail quicker than the retail industry can learn software.

Industrial:

Three words covers all you really need to know about the industrial market: ‘robots’ is one and ‘last mile’ are the other two.

The industrial market is all about automation. Amazon may put out PR pieces about the number of people they employ in warehouses but that is hardly the end game. Complete automation of warehouses is simply a technological challenge. And when you are getting 60 times better at machine learning every three years it is only a matter of time before the best warehouses, run by the best companies, will be entirely dark. Many already are. Many will follow.

It is about more than automation though. A company called Clutter in the US is a new breed of ‘Big Yellow’ type self storage operation. With two differences to the standard operating manual. First, they use AI to help them optimise storage; they don’t store all your goods together but mattresses with mattresses, bicycles with bicycles etc. This means they can utilise their space much more efficiently. And they have their warehouses many miles outside of the cities they serve, where they are cheap. Using an app you can see and track everything you have in store and request delivery within hourly slots. What they lose in proximity they make up for with technology.

Cracking the last mile though, is the big problem the industrial real estate sector needs to help solve. How can we help enable Amazon, or whoever, to get an order to a customer in an hour? And no, Click and Collect is not the answer to that; it is simply a temporary fix that only those in the real estate industry think is an end point.

Alibaba own a supermarket chain in China called Hema. If you live within three kilometres of one of their stores they will deliver to you in…. 30 minutes.

Amazon, even prior to the acquisition of Whole Foods, had a distribution centre within 20 miles of 45% of the US population.

Industrial real estate strategies simply need to focus on those three words. Robots and last mile.

Residential & Build to Rent

Clearly we are not building enough homes, and have not done so for decades. Even if we did they would today be beyond the reach of most young people.

So it is inevitable that the Build to Rent sector will grow, probably dramatically. It has crossed the chasm. Regulatory issues need to be sorted out but I cannot see how they will not be.

This sector has the chance to replace prime offices as the default home of large chunks of institutional money. As we have seen the office market is, for a large percentage of it, dying in terms of providing Bond like returns whereas whilst one can quite easily consider buying office space on-demand that is harder to square with where one lives. As such, stable long term returns should be on offer and might well become the asset of choice to institutions that require stable long term returns.

It is also highly likely, desirable and sensible that large scale build to rent developments will be mixed use and include significant amounts of office or other commercial space. As one does not need to be in a human-centred, deeply collaborative working environment five days a week it makes much sense to add facilities near to where people live.

Hotels

Not my field but demand for Hotels rises inexorably, despite the rise of AirBnb, largely because the world is getting richer and more people are travelling. Barring cataclysmic events, hotels have a strong future. Prosperity, as well as demography, is destiny.

Planning, Design, Construction

If you want one sure bet within the real estate sector then the increasing use of technology in Planning, Design and Construction is it. Together with these silos becoming increasingly joined up. We will not be worrying about the supply of construction workers in ten years. Fortunately, as there won’t be enough. These sectors are being pushed by human constraints and pulled by technological advances. They are only moving in one direction.

In conclusion then we are in a world that Turner would have understood, where everything is a bit of a blur but palpably exciting. Even if we are begrudging in accepting that that is the case, it really is.

Steam engines transformed Victorian society and AI and the 4th Industrial revolution is changing ours. To quote though another great artist, Picasso; ‘Computers are stupid - they can only give you answers’ - it is up to us, their masters, to realise that where we end up, as individuals and as a society, is down to our use of that human skill where we, at least for now, greatly outshine the machines. Judgement. As AI reduces the price of Prediction, the value of Judgement goes up.

And finally, to paraphrase Gary Kasparov, the great chess player and thinker, a human plus a computer, trumps any computer on its own.

Cogito ergo sum

Antony

AI and Real Estate

My presentation, delivered at the Future: PropTech Conference in London on the 2nd May, 2018. 15 minutes.

Or if you prefer to read it .......

Ok, so we are going to talk about Use Cases for AI

The what, the so what, and the now what

To start off I’d like to show you what the 1st industrial revolution felt like to Victorians. This is Rain Steam Speed by Turner, painted in 1844, just after the opening of the Great Western Railway.

Steam engines transformed Victorian society as dramatically as AI is going to transform our society. The future feels like it is coming at us fast and everything is a bit of a blur.

But the excitement is palpable - we are lucky to be living in such fast moving times.

And fast moving they really are.

In January last year McKinsey wrote that 49 percent of all activities people are paid for could be automated by currently demonstrated technology.

Not technology from the future, technology that is available today.

The RICS reported that 88% of the core tasks performed by surveyors could be automated over a ten year period.

So... what is happening to generate all this change?

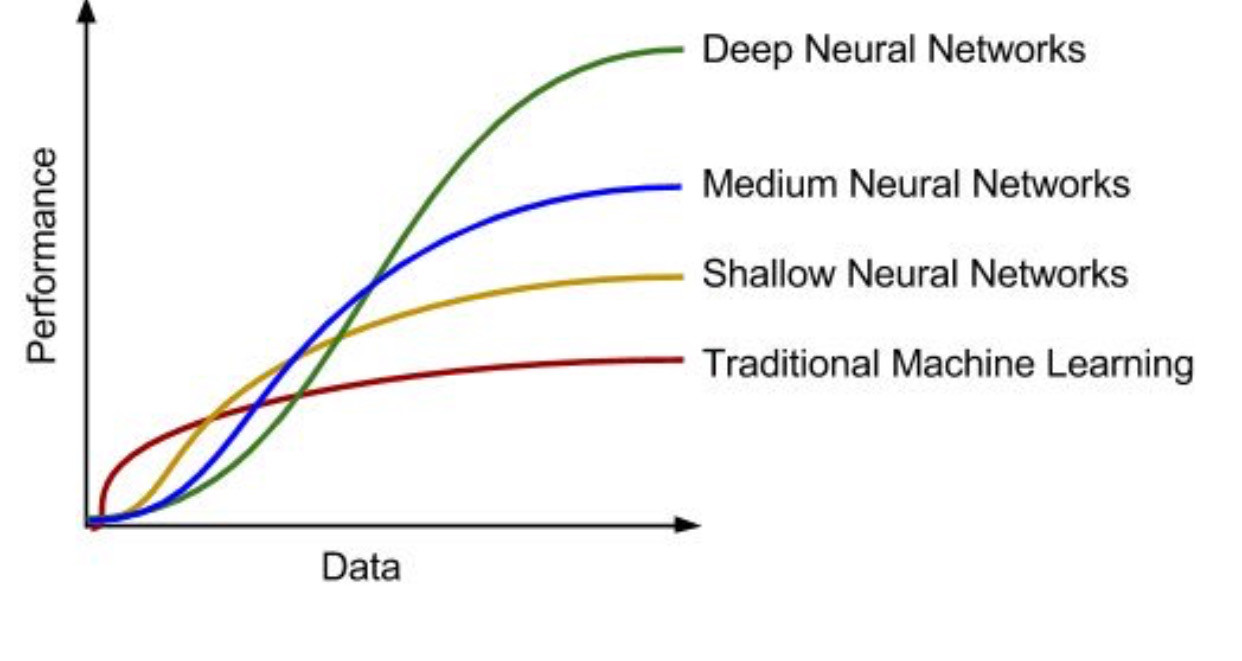

Well the answer starts here. This is Moore’s Law, where essentially computing power doubles every two years, something which has held true for 50 years so far.

So you have 100 thousand transistors on a chip in 1980, 100 million by 2000 and 10 billion by 2016.

This is the archetypal example of exponential growth, the famous hockey stick we hear so much about.

But, compared to the chips that originated in gaming machines but that are now the primary processing units behind AI, this Moore’s Law growth is rather paltry.

Moore’s Law is shown in the two aneamic lines at the bottom. The power of GPU’s has been increasing dramatically faster over the last few years.

Which is why neural network training, which is fundamental to machine learning, became 60 times faster in the three years from 2013 to 2016, with most of that growth in one wonder year, 2015.

So what does this lead to then?

Well for one thing it means computer vision, face recognition etc has gone from being useless to a utility in just a few years.

With error rates of 28% in 2010 it was a pretty useless technology. By 2017, the error rate was down to 2.2%, far better than the 5% which is how humans perform.

And unlike humans, who can only process a few images at a time, computer vision enables 200,000 faces to be recognised in real time.

Likewise speech recognition has gone from useless to utility. In fact it has done so considerably faster than computer vision.

In 2013, we saw word/error rates of 23% - just four years later this was below 5%, again the human level of achievement.

Which is why we have seen all of a sudden the rise of smart speakers like Alexa, and the growing use of Voice as a search interface

It is what happens when new technologies become utilities

So, ALL businesses can now exploit 6 new technological capabilities, made possible by the growing power of AI.

Many more processes can now be automated

We can understand what is happening in pictures and videos

We can optimise complex systems in a manner that was not possible before

And we can automatically generate voice and textual content

And we can automatically understand people using language and make predictions.

Within the real estate industry we have mapped these new capabilities as applying across 17 areas or workflows.

Much of the day to day requirements of the industry can be improved using AI

From investment strategy, to asset monitoring, to customer experience to demand optimisation. The possibilities are almost endless.

But, with AI, there is a catch.

Unlike previous technologies, where often the best policy was to let early adopters make all the mistakes and lose a lot of money, with AI you cannot be a fast follower, and ride on the coat-tails of innovators.

You have to be the innovator

Because AI is all about data and the training of systems. Machine learning means just that - the machines learn from experience and that is a step you cannot buy your way around.

Experience matters in AI. And the rewards go to those who have learnt the most.

So, what then do we do about all of this? How do we apply these powers to real estate?

Well, across real estate there are a number of key things we all have to do.

But really everything boils down to making predictions, and AI is dramatically reducing the cost of prediction. Who will buy, who will sell, what happens if this, what happens if that. What are the chances of etc etc etc

And with better and cheaper predictions, the amount of uncertainty we have to deal with reduces. And less uncertainty is a great enabler. We can take more risks, at less risk.

Here are 9 key Use Case areas for AI in real estate

Computer vision is a powerful weapon. Being able to point a camera at the built environment and to understand what is being seen is a superpower.

But people also like interacting with images. They are comfortable with images. Real estate search using images rather than text will become a big thing.

The internet of things and smart buildings and smart cities, are going to allow us to optimise ‘the space around us’ in unprecedented ways.

Not least of all we are going to be able to optimise our workplaces so that they at last allow us to be as productive as we can be.

All around the world there are now thousands upon thousands of small low altitude satellites and these are allowing us to monitor, inspect and analyse the world in great detail.

We can merge satellite and aerial imagery with other data sets to aid our understanding. From daily monitoring of development sites to checking how full car parks are at shopping centres, there is a lot you can do when you can analyse imagery.

AI is extremely useful in synthesising disparate data sources and finding correlations and causations between them. Automated Valuation Models will become more and more accurate.

And a sidenote on that: As we have said AI can be a winner takes all technology - as with web search we probably only need one automated valuation model in each asset class.

Chatbots are a key AI tool. For anything deeply structured allowing people to text for help or assistance makes a lot of sense. We’ll see a lot of chatbots in property management and customer support.

Location, location, location is of course a real estate mantra but historically we have not really known that much about any given location. AI will allow us to become far better informed about the precise characteristics of locations, and the wants and needs of the people who live, work or shop there.

Voice as a search interface is now becoming commonplace with the likes of Alexa. Expect to see a lot more people talking to computers rather than tapping away at keyboards.

Natural language processing is all about understanding text, and once that becomes a solved problem, all manner of interactions we currently have with text will be changed. Expect to see a rapid decline in human input into report creation for example. Certainly in a business context most reports can be boiled down to a templated format, and auto generated by linking in various data sources.

And finally marketing. Probably the No1 use case for AI across all businesses. Marketing is all about knowing your customer and AI, in various ways, is going to enable us to be much much better at that. Real estate has a lot to learn here. Those who bother to learn will reap big advantages.

So, nine areas where you will find solid use cases for AI in real estate

Here are 70 companies already ready to help you out.

All of this is very exciting but how do you ensure you remain on the right side of this change, and don’t lose your job to an AI?

Well first off you have to remember that Picasso, of course, was right. Computers ARE useless - they can only give us answers.

We are here to put the questions.

This is Gary Kasparov, the great chess master, and also the first world champion to lose to a computer, in his case IBM’s Deep Blue in 1996.

Since that day it was clear that humans would no longer beat computers at chess.

So Gary started a new form of chess, called Advanced Chess. In this a human, sometimes a pair, plus a computer would take on another computer plus a human or a pair.

What transpired was remarkable. First off a human + a computer always beat the computer on its own but also the team who managed the relationship between human and computer, regardless of strength, mostly came out on top.

As he says “weak human + machine + better process was superior to a strong computer alone and, more remarkable, superior to a strong human + machine + inferior process.”

Understanding how to best leverage the different skill-sets of humans and machines is the killer skill.

This was Steve Jobs at the launch of the iPad 2 in March 2011, and shows his famous marriage of ‘technology and the liberal arts’.

“It is in Apple's DNA that technology alone is not enough—it's technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our heart sing.”

So, we have four steps to ensure your job is not taken away by an AI

Step 1 - DO NOT stay in a job that is ‘structured, repeatable or predictable’

This is from the Jack Lemmon film, The Apartment in 1960, and in those days offices were essentially Excel - every desk was like a cell in a spreadsheet where the person working at it was doing something ‘structured, repeatable or predictable.

If your job is anything like that, start planning your exit.

If your office is even anything like this definitely leave your company asap.

Step 2 - You need to learn how to think about AI

You need to Understand what AI is good for, and what it is not good for. Understanding where it can be applied is absolutely foundational and will avoid wasting a lot of time.

You need to look for those use cases - the 88% of core tasks from the RICS report, and the 49% McKinsey referenced.

Amongst those you need to consider which ones are commonplace and repeatable within your own business and/or applicable to many of your customers?

Then you need to think about what data you would need to feed your AI initiatives and whether or not you either have this data, or can acquire it in one way or another

You need to consider whether there are clear metrics by which you could judge success? Is success measurable?

And then finally, if you have all of the above, is that something that will create significant value?

If you get to the end of this with all the right answers then you have a product or service worth pursuing.

If you are looking to build AI solutions for customers then your product or service must abide by these rules.

Thirdly in a world of exponential technology you need to become exponentially human. You need to develop all your human skills - of imagination, empathy, design, social intelligence, problem solving, judgement etc - because that is your value.

Do not try and beat the machines at what they are good at - don’t bring a knife to a gunfight. Instead work on how, with your understanding of AI, you can use it to augment your own human skills.

As prediction becomes cheaper, the value of judgment will increase. All this technology is an input: we are responsible for deciding the output we desire. Those with great judgment, who can weigh up upsides and downsides of predictions will see their value rise.

AI will give us more options: how we exploit them will be down to human judgement.

And think ‘education, education, education’ - in a fast changing world education is a marathon, an ongoing process. You will never run out of new skills to learn.

And then finally you need to deeply consider how AI/Data and all technological change is going to change the world.

There will be winners and there will be losers. Oftentimes each of us will be both. We will lose some things but gain others.

Mostly it is tasks that will be lost rather than entire jobs but there certainly will be many jobs that do become redundant.

There will also be a lot of real estate that becomes redundant: as the work we do changes the nature of the office is going to change fundamentally. Where and how we live as well. And as for retail, well there is much change coming there.

Pay attention to those four rules and your job will not be overtaken by an AI. In fact you will most likely thrive in an AI world.

But either way remember that in business some things don’t change.

The bear is coming but you do not have to be perfect, just better than your peers.

Tweetstorm on OneMarket - Genius move or value chain disrupter? Both

Setting the scene: 'Westfield’s $300M PropTech Spinoff Wants To Give Physical Retail More Power And Data Than Amazon' - https://www.bisnow.com/national/news/retail/westfields-300m-proptech-spinoff-wants-to-give-physical-retail-more-power-and-data-than-amazon-87627

A Tweetstorm re the above

OneMarket spin-off from Westfield is fascinating. And seriously techie. But a two edged sword for ‘customers’. Extensive participation WOULD make EVERYONE better off BUT would also make everyone beholden to OneMarket, who would have great pricing power.

Think Facebook level power within the retail sector. They simply know much much more than you do and you cannot not use them. Hence almost no advertisers have left Facebook.

Big question is whether the large incumbents, @BritishLandPLC @Hammersonplc@LS_Retail are large enough to generate this intelligence on their own?

Large datasets are required for AI but the impact flattens beyond a certain point. Are the incumbents big enough?

Not controlling your own data is the fastest way to fall down the value chain. Incumbent retail landlords IMHO HAVE to go all in on data to stay relevant.

Some go on about being ‘data led’ and then you find out they’ve done a bit of demographic analysis and have footfall stats... you need much more than this.

Who controls your network/ecosystem data will determine who makes the most money. OneMarket could be huge. Just like Rightmove makes the best returns without even being an estate agent.

Might also be why Amazon buy Hammerson, just as Alibaba have bought up shopping centres in China. They have the data and ‘own’ the customer.

For years argued that shopping centres should position themselves as the ‘gateway to a world of wonder’ by implementing deep and extensive curated apps for their centres. Always got kickback that ‘tenants wouldn’t like that’.

But one app that embraces every outlet in a Center, built on deep customer data, would be very powerful. The value proposition to users could be very strong. Instead....

... what you get in most Center apps is 10% off doughnuts or coffee, poor quality images, undifferentiated offers, and zero personalisation of any quality.

It won’t be long before Amazon start shipping us stuff before we’ve been shopping because they ‘know’ what we want. Just return what you don’t want.

What does a shopping Center actually know about their customers? Not nearly enough. If OneMarket flies they could know a very great deal. But....

... who will benefit from that knowledge. Again, think of Facebook. And beware?

Just a thought:)

Antony